Convergence

Card's author :

Jean Michel Cornu

Card's type of licence :

Creative Commons BY-SA

Description :

The tragedy of commons only forecast three possible solutions to this situation:

This simple difference is fraught with consequences. This means that the exchange leads to a multiplication of value and that the land is not as limited as before. As stated nicely by Jean-Claude Guédon, professor of comparative literature at the University of Montreal: "A digitized bird knows no cage."

Yet the expression "gift economy" must not be understood as a kind of utopia that push each one to become altruistic even if it goes against personal interest. It is rather an asymmetric mode of exchange. When monetizing a property has no meaning because it is abundant and easy to find, and when all minimum needs for survival are fullfiled, the only thing that we can still look for is the esteem of the community. The fact that the counterpart of the gift goes through all the other members helps the convergence of individual and collective interests.

On certain tropical islands, the food is plentiful. Marcel Mauss studied the implementation of the gift and his various characteristics4.

Closer to us, the scientific community has had for a very long time the habit of sharing all its discoveries. The colloquiums are the opportunity occasion to present to all its results and to gain consideration and esteem from it.

The community of free software developers followed a similar path. It was a question at the beginning of researchers working in diverse laboratories and universities (they thus benefited from a relative material safety). They applied successfully the same methods as the scientists in the field apparently more industrial of software.

Finally, the small community of the particularly rich people spends a lot of time getting involved in great humanitarian causes to gain the respect of their fellow contemporaries.

Drifts are thus observed when one or more characteristics specific to a gift are not respected. The gift economy is simply governed by different rules than the consumption-based economy.

If patents, copyrights and fashion rights are aiming to protect creation, they must be however scanned very carefully not to become a weapon against abundance and... creation.

We will see later the rules to establish a self-regulating mechanism for evaluation.

Thus, it is not necessary to expect altruism from all to implement projects involving cooperation. Donors get benefits that are simply more subtle to understand because they are part of a two stroke logic.

Given unit.

Exchanges of intangible property would normally lead to a multiplication of value and to their abundance. It is often possible to make choices that lead to shortages or to abundance.

There are rules of the gift which if they are not respected lead to deviations:

That kind of situation happens quiet often. When we ignore how somebody can react, we consider the case of a betrayal (or more simply the case of lack of cooperation). In this case the other doesn't play the game, the least bad situation for us is not to play ourselves. However, from a global point of view, the gain is much more important if we both cooperate.

The simulations done so far show that the most effective solution is to start by cooperating and then to copy one's behavior on the other's: if he cooperates, we also cooperates, if he betrays, we do the same.

More specifically, the most effective strategy was discovered in 1974 by the philosopher and psychologist Anatol Rapaport [RAP] quoted by Bernard Werber 7: it is the CRF method (Cooperation-Reciprocity-Forgiveness). In this case we start by cooperating and then depending on what the other person does we copy his behavior, and finally we reset counters being ready to cooperate again. This approach is the most efficient to help someone who has betrayed once to understand both that you will not let her do and that you're ready to go forward on a cooperative basis.

To enable these interactions to happen, there is a need to spend enough time together. The very definition of a community is to gather people for a long time and to create a relationship between them which is based on confidence.

Again, by proposing new game's rules doesn't mean that everyone will become an altruist. Thus for communities there are risks to produce opposite results than those expected.

Starting up a community is a prerequisite. The benefits of the community are not there yet, and the multiple steps that could help to break the prisoner's dilemma have not yet operate.

The sociologists call distance of horizon 8, the lap of time during which people think theywill be together. This very subjective notion is a key factor for wether people will cooperate or not. There is thus much less robberies in small local stores even when the store has just started up, than in large anonymous and undifferentiated supermarkets. Perceived consequences of an act are different according to the story we can later share with the persons concerned.

Of course, it is not an absolute rule. Everyone doesn't act at best for his own interests because the CRF method is not assimilated by everyone. But the vision of a common future favors cooperation while the lack of long-term horizon promotes opposite behaviors.

The more people have had positive experiences of cooperation around them by seeing other people starting to cooperate, the more they assimilate the CRF method and the easier it is to set up a community.

If past ordeals are forgotten, the group returns to the more dangerous situation of the community's starting up.

With the exchanges studied in the previous chapter, inheritance is the second foundation of human society according to Maurice Godelier 9: "Our analyses leads us to conclude that there cannot be a human society without two domains, the one of exchanges, whatever and however we exchange, from gift to potlatch, from sacrifice to sale, purchase, market, and the one where individuals and the groups keep preciously for themselves things, narratives, names, ways of thinking, and then transmit them to their progeny or to those who share the same faith. Because what we keep always constitutes "facts" which drive the individuals and the groups back to another time, back and in front of their origins.

We will see that the fundamental tasks of the coordinator is to develop a history capitalizing the common heritage

In addition to the relations which are gradually established within the community, the community is also based on the sense of belonging. The implementation of "rituals" and common references are also a foundation on which is built the collective heritage.

René Girard 10 depicts a collective behavior anchored in the human behavior which backs up the integrity of the community thanks to the sacrifice of a "scapegoat". The mimetic cycle which he describes occurs in several stages.

Conflict often begins with a "mimetic desire" of wanting what the other has.

When a conflict occurs (and it occurs of course more or less frequently), the person who feels betrayed often has an aggressive attitude. Whether we recognize it or not we have a natural tendency to mimicry and our behaviors take after the others' (even if you don't accept it, advertisers have understood that very well). By imitation, the other person takes an aggressive stance and then gets involved in what psychologists sometimes call the "verbal ping-pong" where the goal is to kill the other's stubbornness with stubbornness, each one pumping energy from the other.

The third step is the spreading of the spirit of aggression, always by imitation, to the whole community and conflicts are increasing. This mechanism is very well described in the comics "Asterix and the Roman Agent." As aggressive reactions increase, the group influences behaviors and engenders a self-cumulative effect.

When the tension in the group reaches a dangerous level that threatens its integrity, either there is a split, each choosing one side or another, or the group voids all aggression through a "scapegoat ". He is preferably selected from outside the conflicts which have no other links between them than the mimetic effect. He is often a weaker and very different person on whom all aggressiveness will strive irrationally.

Once the overflow of aggression is spilled, the scapegoat is "demonized" as the source of all evils to justify the reunification of the group over its destruction and to forget the circumstances of the "sacrifice". The reconciled group has saved his integrity by sacrificing an innocent scapegoat. Oblivion allows the group to resume its course until the next cycle.

René Girard goes on showing that the mechanism of victimization that puts victims at the center of our attention is firmly rooted in our Judeo-Christian civilization. Our data strongly focus on the consequences for the victims, which was not the case in earlier times. This process has a beneficial effect because it prevents the blindness and forgetfulness required to operate the imitative cycle.

Clarifying the mechanism of "scapegoat" can break the imitative cycle. It does not prevent the rise of tension and it is necessary to find a more acceptable new safety valve. The chapter on resolution of conflicts proposes some additional thoughts.

Mimicry of human kind has not only negative effects. It can be seized in a positive way, such as the possibility to spread the CRF method in the community "by the example."

It doesn't mean that frontiers between the inside and the outside of the community can't exist. The feeling of membership and the existence of peculiarities specific to the group are essential for its existence. But it can grow rich only by remaining open on the outside.

However, there are two criteria that promote the opening of the group to the outside:

Each participant must be able to leave at any moment.

Belonging to other groups should be allowed and even encouraged to enrich the group through these informal links.

A community multiplies the opportunities and experiences and thus promote convergence towards cooperation.

There are rules to prevent the community from deviating:

Indeed, when someone is appointed to a position and fulfills his task, he is promoted to a new position. The process continues, allowing him to practice his skills on increasingly complex tasks until he reaches a position where he has reached his "level of incompetence". He is then no longer able to fulfill his role as well and is no longer promoted. He then remains stuck to the position where he is the less competent.

This case is just one of many paradoxes that arise when one wishes to evaluate human labor as objectively as practical and scientific facts. From this point of view, the work of Taylor who made the most scientific planning is more adapted to machine than man. At the time this work was published, many people were working machines. Today, the machines are sophisticated enough to take over the most repetitive and schedulable work. In return, the task of creating, as well as those requiring high scalability and subjective estimation are undergoing a strong development.

There is absolutely no denying any evaluation but rather to find new methods that apprehend human characteristics better: subjectivity, motivation or lack of motivation, good or bad faith. These different criteria are peculiar because not measurable even if they can be estimated to a certain extent. So this is a true revolution in the evaluation systems in a world based on objective measures since the XVIIth century. However, we see that the same subjective evaluations can produce phenomena of regulation and self-correction that is their mainspring.

Usually, in the industrial projects submitted to a call for tenders for example, the first and the last goals outdo. The investment of a representative being heavy, he tries to know beforehand if his money is well invested. During the project, he tries to correct it so that the project goes on well. Then finally, he assess if the result can be used for further stages (broadcasting of the results or basic contribution to another project following a ''taylorized'' assembly-line).

Ideally, the title given is not exclusive and does not give special power. A "binding agent with the Spanish-speaking world" (which does not preclude having other) is better than a "person in charge of translations into Spanish''.

Similarly the final assesment is often about assessing the realization of what was expected beforehand rather than judging its usefulness and the use that is made afterwards.

Assesment during the progress of the project may instead provide a mechanism for self-correction afterwards to maximize the use made of the results already achieved by the project. Potential contributors will be involved according to their personal evaluation of the project, of the coordinator and of what they can gain from the results.

A very interesting approach was initiated by the United Nations Program for Development with a Human Development Index based on several criteria which approximate at best the object that is to be evaluated.

These criteria apprehend: health, education and economics.

This is probably our best today to assess human development in a country with an objective indicator, but each rate itself is a mean and only objective, measurable criteria are taken into account. It is then possible to educate better a privileged part of the population or to enroll without seeking to increase school performance indices. Multiplying criteria only makes the task more subtle for those who only strive to adapt their performance to optimize the values of each criterion. But it gives less chance to fulfill at the very best the specific criteria to the indicator for those who very honestly focus primarily on causes.

The traditional methods of objective measures achieved with the scientific advances of the XVIIth century itself require developments to go beyond simple means: sometimes we add standard deviations to average rates (average deviations from the mean). If it gives an idea of the scale of differences, some more subtle points are not taken into account, for example the homogeneous distribution of a population or the division into two or more groups more or less privileged with little chance to move from one group to another.

Side effects (the extreme limits) can also disturb simple objective laws (for example, monopolies). You must have an idea of what happens far from balance and even on limits.

The problem comes from impossibility to measure good faith objectively. It is only possible to obtain a measurable objective assessment afterwards and with greater or lesser margin between the measured result and the evaluation criteria.

Agrreing on the reintroduction of a subjective evaluation, such as the one provided by the esteem brought by a project, is essential. To lessen difficulties, it is important that it should be decentralized and global and obtained by the whole community and the outside world.

In a cooperative project, we try to obtain the cooperation of the members and to coordinate their works to get a result. The power of constraint (hierarchical or contractual power), is not any more in the center of the management of the project. The end of the power of constraint allows an auto-regulated evaluation.

The pure and simple abolition of the coercive power may seem a heresy heading to the " field of mud " of the tragedy of commons. We will see on the contrary that in an appropriate environment, it allows to get out of usual paradoxes.

When we are not "forced to cooperate" any more, each one gets involved or uses the results according to what he sees of the project. If globally, the project generates esteem, it will develop more and more. The evaluation is then subjective, post factum and continuous by the whole community of the contributors and of the users. The whole creates a virtuous circle.

The power of the coordinator is limited to the ability of integrating or not the proposed changes by the contributors and possibly exclude a person from the community he established. For what's left, he can only encourage people to become user or contributor, with no power to compel them.

Collaborative projects are well suited to projects between structures or inter-service projects. The running of associations sometimes allow to develop non-hierarchical projects of this kind.

The complete abandonment of power of constraint given by the title or the employment contract is replaced by the incentive to cooperate with the results obtained and esteem. This is a major difference with the conventional project management. It is therefore not easy to follow both approaches simultaneously. We will see in the chapter on mixing methods that projects using fully or partially the power of constraint can simply give some advantages in promoting the greatest possible post factum long term and subjective evaluation by the community.

This can be achieved by giving up the power of constraint and by letting esteem for the project and its members do its self-regulation job.

1 HARDIN, Garrett. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science [online]. 13 December 1968. Vol. 162, no. 3859, p. 1243–1248. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. DOI 10.1126/science.162.3859.1243. Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/162/3859/1243The population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality.PMID: 17756331

2 RAYMOND, Eric S. Homesteading the noosphere. First Monday [online]. 1998. Vol. 3, no. 10. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/621

3 "Hardin later recognized that much of his characterization of the negative aspects of the commons, which according to his analysis 'remorselessly generates tragedy'... was based on a description, not of a commons regime in which authority over use of the resources resides within the community, but of an open access regime, unregulated by any external authority or social consensus" : WARNER, Gary. Participatory Management, Popular Knowledge, and Community Empowerment: The Case of Sea Urchin Harvesting in the Vieux-Fort Area of St. Lucia. Human Ecology [online]. 1 March 1997. Vol. 25, no. 1, p. 29–46. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. DOI 10.1023/A:1021931802531. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A%3A1021931802531

4 MAUSS, Marcel and WEBER, Florence. Essai sur le don: forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques. Paris, France : Presses universitaires de France, 2007. Quadrige. Grands textes, ISSN 1764-0288. ISBN 978-2-13-055499-8.

5 GODELIER, Maurice. L’énigme du don. Paris, France : Fayard, impr. 1997, 1997. ISBN 2-213-59693-X.

6 See the journal "Pour la Science" which edits an article on the prisonner's dilemma every six months (Scientific American). Pour la Science - Le magazine de référence de l’actualité scientifique. [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://www.pourlascience.fr/

Voir aussi Le dilemme du prisonnier. [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://web.archive.org/web/20050302205551/http://www.apprendre-en-ligne.net/jeux/dilemme/home.html

7 WERBER, Bernard. L’encyclopédie du savoir relatif et absolu. Paris, France : Albin Michel, 2000. ISBN 2-226-12041-6.

8 GLANCE, Natalie and HUBERMAN, Bernardo. La dynamique des dilemmes sociaux. Pour la science [online]. 1994. No. 199, p. 26–31. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=4210574

9 GODELIER, Maurice. L’énigme du don. Paris, France : Fayard 1997. ISBN 2-213-59693-X.

BLONDEAU-COULET, Olivier and LATRIVE, Florent (eds.).

Libres enfants du savoir numérique: une anthologie du “Libre.”Paris, France : Ed. de l’Eclat, impr. 2000, 2000. Premier secours. - Perreux : L’Eclat. ISBN 2-8416-2043-3.

BARBROOK, Richard. L’économie du don High Tech. [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://web.archive.org/web/20090917124333/http://www.freescape.eu.org/eclat/2partie/Barbrook/barbrook2.html

10 GIRARD, René. Je vois Satan tomber comme l’éclair. Paris, France : B. Grasset, 1999. ISBN 2-246-26791-9.

11 GUYARD, Jacques, BRARD, Jean-Pierre and FRANCE. ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE. Rapport fait au nom de la Commission d’enquête sur la situation financière, patrimoniale et fiscale des sectes, ainsi que sur leurs activités économiques et leurs relations avec les milieux économiques et financiers. Paris, France : Assemblée nationale, 1999. Les Documents d’information - Assemblée nationale (Texte imprimé), ISSN 1240-831X ; 1999, 33. ISBN 2-11-108354-2.

12 "in a hierarchy, every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence." : PETER, Laurence J and HULL, Raymond. The Peter principle: why things always go wrong. New York : Bantam, 1969. ISBN 9780553244151.

See also an interview of J. Peters : The Peters Principles. Reason.com [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://reason.com/archives/1997/10/01/the-peters-principles

Source: CORNU, Jean-Michel. La coopération, nouvelles approches. http://www. cornu. eu. org/texts/cooperation [online]. 2004. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://fing-unige.viabloga.com/files/cooperation2.pdf

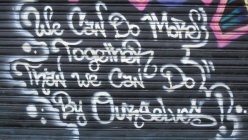

Photo credits : StephanieHobson sur Flickr - CC-BY-SA

Facilitating convergence in an environment of abundance with commons

Paradox of the tragedy of the commons

In a text now famous "The tragedy of the commons" 1, Garret Hardin presents the three unique solutions to live together with a set of goods to share. He describes a field, joint property of the village. The farmers 's cattle graze on it . It browses grass and deteriorates this common leaving behind muddy plots. Without a thorough application of policies, the interest of every farmer is to take advantage as quickly as possible of the field by sending on it the maximum animal that will make the most of it before the whole field is a sea of mud.The tragedy of commons only forecast three possible solutions to this situation:

- The field becomes a large field of mud

- A person who has a power of constraint allocates resources on behalf of the village

- The field is divided into plots managed by each farmer who has a right of property.

The limits of the tragedy

To reconcile the individual and the collective interests does not seem obvious in the scenario described in the tragedy of commons (otherwise, we would live better for a long time!). Nevertheless, if Hardin concludes in its work that the only solutions to the lack of men's responsibilities are the privatization of commons and/or the interventionism of the state, he recognizes later that his basic premise is not always valid. His colleague Gary Warner indicates: " Hardin recognized later that the characterization of the negative aspects of the common goods was based on a description... an open (regime), not regulated by an external authority or a social consensus 3.Without destruction the territory is not limited any more

There are other cases which lead to different conclusions: in the tragedy of commons, the cattle eats the grass and destroys gradually the field. In the field of intangible assets such as software, contents, art or knowledge, the rules are intrinsically different: the reading of a text does not destroy it, to give an information to somebody does not mean that we don't have it anymore.This simple difference is fraught with consequences. This means that the exchange leads to a multiplication of value and that the land is not as limited as before. As stated nicely by Jean-Claude Guédon, professor of comparative literature at the University of Montreal: "A digitized bird knows no cage."

A new notion of property

The notion of property does not disappear for all that. For example in the development of freeware, rather often, a person detains the right to integrate the modifications proposed by all. Raymond calls him the " benevolent dictator. " But everybody can come to use, copy or redistribute freely the software produced collectively. Everybody can circulate freely on the territory of the owner and it is exactly what gives it value.A new notion of economics

The economy itself was based on exchanges between the two protagonists (the transaction), and on consumption in the end by what the experts call "the final destructor" (the consumer.) If we want to understand better the rules of commons, we will extend the current analysis to take into account: the collective exchanges (with a global rather than elemental balancing) and the non-consumptive use of property.The gift economy

One of the examples of economy which is not based on transaction, looks a priori very much like a utopia. It is the gift economy such as we find it in some very specific environments.Yet the expression "gift economy" must not be understood as a kind of utopia that push each one to become altruistic even if it goes against personal interest. It is rather an asymmetric mode of exchange. When monetizing a property has no meaning because it is abundant and easy to find, and when all minimum needs for survival are fullfiled, the only thing that we can still look for is the esteem of the community. The fact that the counterpart of the gift goes through all the other members helps the convergence of individual and collective interests.

Abundance: source of gift

One of the key elements that favors a shift from exchange economy towards gift economy is the shift from rarity to abundance. The abundance means that players have solved their security needs and they are looking for something else such as recognition. Abundance can exist, as seen before, in the field of intangible assets and in the field of knowledge...Some examples of gift economy

There are different communities that benefit both from material safety and abundance. In these cases, these communities have seen naturally the emergence of a gift economy.On certain tropical islands, the food is plentiful. Marcel Mauss studied the implementation of the gift and his various characteristics4.

Closer to us, the scientific community has had for a very long time the habit of sharing all its discoveries. The colloquiums are the opportunity occasion to present to all its results and to gain consideration and esteem from it.

The community of free software developers followed a similar path. It was a question at the beginning of researchers working in diverse laboratories and universities (they thus benefited from a relative material safety). They applied successfully the same methods as the scientists in the field apparently more industrial of software.

Finally, the small community of the particularly rich people spends a lot of time getting involved in great humanitarian causes to gain the respect of their fellow contemporaries.

Abundance is abundant

The affected field is larger than we imagine. If tangible assets seem limited for a majority of people, it can be otherwise with intangible assets. So the proverb of Kuan-Tseu " If you give a fish to a man, he will be fed once ; if you teach him to fish, he will be fed all his life ". The fish is a consumer good which can be rare if there is a shortage or few fishermen. Learning to fish is on the contrary a knowledge which becomes more and more plentiful every time a person teach another person to fish..Rules of gift

But all is not a bed of roses in the world of gift and abundance. You don't make an altruistic out of everyone just by changing the rules of the game.Drifts are thus observed when one or more characteristics specific to a gift are not respected. The gift economy is simply governed by different rules than the consumption-based economy.

First deviation: Maintaining the shortage

One of the first deviation is to manufacture shortage artificially in order to return to the better known rules of consumption economy. This is common on physical goods such as oil. It is also possible to make "usable" or more precisely "obsolete" intangible goods. The software industry has been very good at it and now in France the tax administration considers that it takes one year to a software to pay for itself, much less than hardware!If patents, copyrights and fashion rights are aiming to protect creation, they must be however scanned very carefully not to become a weapon against abundance and... creation.

First rule: Abundance is safe and well shared

The project has to concern a good which can become plentiful to favor gift economy. This should be the case of non-consumable intangible assets (knowledge, software, content ...). In this case, the exchange results in a multiplication of the value. The switch to an economy of abundance or scarcity doesn't only depend on the abundance of the initial good but also on the mechanisms of sharing and protection.Second deviation: Giving to crush others

Despite the altruism that gift economy "seems to show", it is nothing more but an economy with rules neither better nor worse, simply different. Maurice Godelier describes the rules of a particular gift: the potlatch. It is a sacred act , either a gift or a destruction, a kind of challenge for the one who gets it to do the same. " In the potlatch, we give to crush the other with our gift. We give him much more than he can give back or much more than he gave us 5.Second rule: Evaluation is global and decentralized

The other big change is in evaluation. It is decentralized, done by all members and on the whole of the gifts done. That is very different from trading where each deal is valued. Consequently, evaluation is there empirical and depends on each of us. It can't be mesured because it is not possible to compare gratefulness with a precise and given unit.Examples of benchmarks

In trading, "benchmarks'' are more and more frequent and widespread in global markets, any of us can more or less understand their evolution. In gift economy, each one has his own "benchmarking system" according to his own criteria. But the group phenomenon could generate the rise of locally recognized benchmarks.We will see later the rules to establish a self-regulating mechanism for evaluation.

Third deviation: Claim for one's due

Another deviation is to ask back for one's gift to the person or the family who received it, instead of waiting to receive it from the whole of the pears. This deviation is often seen in African families which have otherwise a great tradition of solidarity and cooperation.Third rule: A not requested compensation – a two stroke mechanism

The third thing which changes in the gift economy is what the donor earns. In trading, the one who gives the good asks in exchange for another equivalent good or for a representation of the value of the good (some money). With a gift, the donor doesn't expect anything back from the receiver or anyone else. He gets later the gratitude of the whole community, which will not estimate each gift but the whole of what he gave. In a second stage this gratitude brings him advantages as we shall see it farther.Thus, it is not necessary to expect altruism from all to implement projects involving cooperation. Donors get benefits that are simply more subtle to understand because they are part of a two stroke logic.

Given unit.

Summary

A gift economy arise when commons are plenty. This involves new notions of property and economy.Exchanges of intangible property would normally lead to a multiplication of value and to their abundance. It is often possible to make choices that lead to shortages or to abundance.

There are rules of the gift which if they are not respected lead to deviations:

- The abundance must be protected and well shared to avoid the return in an consumer economy.

- The evaluation must be global and decentralized so that no particular gift is used for crushing someone.

- The compensation must not be requested from the receiver to avoid debts...

Facilitating convergence by giving a long term vision

The prisoner's dilemma

The example of the prisoner's dilemma is a paradox where people can act against their own interest. A thief and his accomplice are caught by the police. Each one can choose to betray or not but they don't know beforehand each other's reaction. In this case, if both agrees, they will pu through much better. But one might be tempted to betray his accomplice to avoid being the only accused, in case of betrayal. By his denunciation he can also get a relieved punishment. Very often, when in doubt, the two prisoners denounce each other and they both end up losers 6.That kind of situation happens quiet often. When we ignore how somebody can react, we consider the case of a betrayal (or more simply the case of lack of cooperation). In this case the other doesn't play the game, the least bad situation for us is not to play ourselves. However, from a global point of view, the gain is much more important if we both cooperate.

The CRF method

The prisoner's dilemma was studied within the framework of games theory... Lacking information on the other's behavior, the least bad individual answer is against general interest. However, the results change when there is more than a single event, but several iterations. In this case, each can gradually get information on how the other responds.The simulations done so far show that the most effective solution is to start by cooperating and then to copy one's behavior on the other's: if he cooperates, we also cooperates, if he betrays, we do the same.

More specifically, the most effective strategy was discovered in 1974 by the philosopher and psychologist Anatol Rapaport [RAP] quoted by Bernard Werber 7: it is the CRF method (Cooperation-Reciprocity-Forgiveness). In this case we start by cooperating and then depending on what the other person does we copy his behavior, and finally we reset counters being ready to cooperate again. This approach is the most efficient to help someone who has betrayed once to understand both that you will not let her do and that you're ready to go forward on a cooperative basis.

Enabling the maximum opportunities of long term interactions

From these two examples, we can see that when the experience is unique, the trend is betrayal, whereas a strategy heading towards cooperation becomes possible when attempts are reiterated.To enable these interactions to happen, there is a need to spend enough time together. The very definition of a community is to gather people for a long time and to create a relationship between them which is based on confidence.

A community for a long term cooperation

One of the most effective manners to make people cooperate is to create a spirit of community. It involves a feeling of membership and a mutual confidence(trust) between the members.Again, by proposing new game's rules doesn't mean that everyone will become an altruist. Thus for communities there are risks to produce opposite results than those expected.

First danger: The community dies before having a past

The starting up of a community is the most sensitive time. When the interactions between community members grow, betrayals naturally occur which lead to conflict.Starting up a community is a prerequisite. The benefits of the community are not there yet, and the multiple steps that could help to break the prisoner's dilemma have not yet operate.

Firts rule: Giving people a long-term vision

We have seen that the optimum method was to start cooperation (even if it means acting differently according to others' reactions). It is therefore possible to promote cooperation between people who have no common past if these people have the knowledge that they will spend time together agin in the future.The sociologists call distance of horizon 8, the lap of time during which people think theywill be together. This very subjective notion is a key factor for wether people will cooperate or not. There is thus much less robberies in small local stores even when the store has just started up, than in large anonymous and undifferentiated supermarkets. Perceived consequences of an act are different according to the story we can later share with the persons concerned.

Of course, it is not an absolute rule. Everyone doesn't act at best for his own interests because the CRF method is not assimilated by everyone. But the vision of a common future favors cooperation while the lack of long-term horizon promotes opposite behaviors.

The more people have had positive experiences of cooperation around them by seeing other people starting to cooperate, the more they assimilate the CRF method and the easier it is to set up a community.

Second danger: The lost past

When we have spent some time with people, many ordeals based on the prisoner's dilemma have occurred. If the group has not died of these tribulations, it strengthens progressively. But one of the peculiarities of human being is the ability to forget. This function is essential not to overload the brain with every useless experiments. But gradually as cooperation sets up, the idea of danger recedes and the memory considers the past ordeals as lower priority events.If past ordeals are forgotten, the group returns to the more dangerous situation of the community's starting up.

Second rule: History is the basis

The legacy of the group is a key element to enable it to keep on building cohesion rather than rgoing back to the dangerous point of departure.With the exchanges studied in the previous chapter, inheritance is the second foundation of human society according to Maurice Godelier 9: "Our analyses leads us to conclude that there cannot be a human society without two domains, the one of exchanges, whatever and however we exchange, from gift to potlatch, from sacrifice to sale, purchase, market, and the one where individuals and the groups keep preciously for themselves things, narratives, names, ways of thinking, and then transmit them to their progeny or to those who share the same faith. Because what we keep always constitutes "facts" which drive the individuals and the groups back to another time, back and in front of their origins.

We will see that the fundamental tasks of the coordinator is to develop a history capitalizing the common heritage

In addition to the relations which are gradually established within the community, the community is also based on the sense of belonging. The implementation of "rituals" and common references are also a foundation on which is built the collective heritage.

Third danger: The imitative cycle

It's hard for us admitting that besides our individual behavior which we believe we control, we are submitted to collective behavior. The sways in the crowd and the reactions of panic are familiar to us for because we saw them in movies or sometimes undergone them. But it seems impossible to us to do the same things which we believe are nonsense simply by mimicry.René Girard 10 depicts a collective behavior anchored in the human behavior which backs up the integrity of the community thanks to the sacrifice of a "scapegoat". The mimetic cycle which he describes occurs in several stages.

Conflict often begins with a "mimetic desire" of wanting what the other has.

When a conflict occurs (and it occurs of course more or less frequently), the person who feels betrayed often has an aggressive attitude. Whether we recognize it or not we have a natural tendency to mimicry and our behaviors take after the others' (even if you don't accept it, advertisers have understood that very well). By imitation, the other person takes an aggressive stance and then gets involved in what psychologists sometimes call the "verbal ping-pong" where the goal is to kill the other's stubbornness with stubbornness, each one pumping energy from the other.

The third step is the spreading of the spirit of aggression, always by imitation, to the whole community and conflicts are increasing. This mechanism is very well described in the comics "Asterix and the Roman Agent." As aggressive reactions increase, the group influences behaviors and engenders a self-cumulative effect.

When the tension in the group reaches a dangerous level that threatens its integrity, either there is a split, each choosing one side or another, or the group voids all aggression through a "scapegoat ". He is preferably selected from outside the conflicts which have no other links between them than the mimetic effect. He is often a weaker and very different person on whom all aggressiveness will strive irrationally.

Once the overflow of aggression is spilled, the scapegoat is "demonized" as the source of all evils to justify the reunification of the group over its destruction and to forget the circumstances of the "sacrifice". The reconciled group has saved his integrity by sacrificing an innocent scapegoat. Oblivion allows the group to resume its course until the next cycle.

Third rule: Clarifying the ''scapegoat mechanism''

One of the difficulties in understanding the mechanism of imitative cycle is precisely due to the fact that it can only work in en environment of unawareness. Participants of this cycle can't accept the mimicry of their behavior, nor its irrational climax up to the spill of aggressiveness on an innocent and moreover the mechanism of oblivion of this atrocity.René Girard goes on showing that the mechanism of victimization that puts victims at the center of our attention is firmly rooted in our Judeo-Christian civilization. Our data strongly focus on the consequences for the victims, which was not the case in earlier times. This process has a beneficial effect because it prevents the blindness and forgetfulness required to operate the imitative cycle.

Clarifying the mechanism of "scapegoat" can break the imitative cycle. It does not prevent the rise of tension and it is necessary to find a more acceptable new safety valve. The chapter on resolution of conflicts proposes some additional thoughts.

Mimicry of human kind has not only negative effects. It can be seized in a positive way, such as the possibility to spread the CRF method in the community "by the example."

Fourth danger: The closed community

The fourth danger for a community is to close on itself. The group can keep on improving but by cutting itself from the world outside, there is a risk of developping a sectarian behavior harmful to its members.It doesn't mean that frontiers between the inside and the outside of the community can't exist. The feeling of membership and the existence of peculiarities specific to the group are essential for its existence. But it can grow rich only by remaining open on the outside.

Fourth rule: Allowing withdrawal and multi-membership

It is not always easy to find objective criteria to qualify a group open or closed. A survey on sects conducted by the French parliament 11 recommands tax audits on suspicious movements as they often are intended to bring wealth and power to a presumed guru.However, there are two criteria that promote the opening of the group to the outside:

Each participant must be able to leave at any moment.

Belonging to other groups should be allowed and even encouraged to enrich the group through these informal links.

Summary

If the dominant strategy in the case of a single event is often betrayal, the method CRF (Cooperatio, Reciprocity, Forgiveness) is the most efficient when numerous common and iterative experiences occur.A community multiplies the opportunities and experiences and thus promote convergence towards cooperation.

There are rules to prevent the community from deviating:

- Give everyone a long-term vision

- Enable the development of such behaviors as CRF

- Develop a history to preserve the common heritage

- Avoid a ''going back to zero"

- Clarify the mechanism of imitative cycle and find another safety valve

- Eradicate the focus on a "scapegoat"

- Allow everyone to leave at any time and encourage membership in other groups

- In order to avoid sectarisation as in closed group

Facilitate convergence by establishing mechanisms of esteem

The Peter's principle

Laurence J. Peter studied the paradoxes which urge an organization going from bad to worse. His most known principle indicates that "In a hierarchy, every person tends to rise until she gets to her level of incompetence" 12Indeed, when someone is appointed to a position and fulfills his task, he is promoted to a new position. The process continues, allowing him to practice his skills on increasingly complex tasks until he reaches a position where he has reached his "level of incompetence". He is then no longer able to fulfill his role as well and is no longer promoted. He then remains stuck to the position where he is the less competent.

This case is just one of many paradoxes that arise when one wishes to evaluate human labor as objectively as practical and scientific facts. From this point of view, the work of Taylor who made the most scientific planning is more adapted to machine than man. At the time this work was published, many people were working machines. Today, the machines are sophisticated enough to take over the most repetitive and schedulable work. In return, the task of creating, as well as those requiring high scalability and subjective estimation are undergoing a strong development.

There is absolutely no denying any evaluation but rather to find new methods that apprehend human characteristics better: subjectivity, motivation or lack of motivation, good or bad faith. These different criteria are peculiar because not measurable even if they can be estimated to a certain extent. So this is a true revolution in the evaluation systems in a world based on objective measures since the XVIIth century. However, we see that the same subjective evaluations can produce phenomena of regulation and self-correction that is their mainspring.

Evaluation of conventionnal projects

The purpose of assessment in a conventional management project is triple :- Know beforehand whether a project can be given to someone or to a team

- Ensure that the project is corrected along its development to improve results

- Assess the project post factum to see if it was successful

Usually, in the industrial projects submitted to a call for tenders for example, the first and the last goals outdo. The investment of a representative being heavy, he tries to know beforehand if his money is well invested. During the project, he tries to correct it so that the project goes on well. Then finally, he assess if the result can be used for further stages (broadcasting of the results or basic contribution to another project following a ''taylorized'' assembly-line).

First deviation : Beforehand assesment

Often to attract contributors, they are given a "title" in the project. It often helps to motivate the person by bringing recognition from the very start. Beware though, titles have three dangers :- It's a beforehand recognition which places us in the Peter's Principle

- They often give a coercive hierarchical power.

- They are dangerous when operating because they block a role that can not easily be taken over by another if necessary.

Ideally, the title given is not exclusive and does not give special power. A "binding agent with the Spanish-speaking world" (which does not preclude having other) is better than a "person in charge of translations into Spanish''.

First rule: Assess after the event (post factum)

Let's assume that a project is developped in an environment of abundance, the minimum necessary for its survival needs are fullfiled and that there is sufficient time to allow the group to mature at its own pace. In this case, the beforehand assesment is far less important (except perhaps for the one in charge of the project who must decide whether to launch it or not). In this case it is more useful to correct the project along its development.Similarly the final assesment is often about assessing the realization of what was expected beforehand rather than judging its usefulness and the use that is made afterwards.

Assesment during the progress of the project may instead provide a mechanism for self-correction afterwards to maximize the use made of the results already achieved by the project. Potential contributors will be involved according to their personal evaluation of the project, of the coordinator and of what they can gain from the results.

Second deviation: Limited assesment

The assesment is usually done at specific times, just like a photo of the project, sometimes only before and after the project. In this case, it doesn't apprehend human evolutions that even small at the start may swell quickly then suddenly switch to cooperation or betrayal. It does not allow to seize opportunities early enough at the source.Second rule: Continuous assesment

When allowing continuous assessment, we enable the emergence of vicious or virtuous circles "that will magnify until a brutal change of behavior. According to the observers' insight (and we will see in the next section that many people are better than one in this case), differences can be detected early enough to act accordingly.Third deviation: Assesment by a reduced number of persons

Often, the project is assessed by representatives who want to know if their money is well invested. The evaluation is done by an external person (an agent) which ''only needs'' to be convinced with a well presented report on what will be done or the expected results. Of course during and at the end of the project, actual results are also included in the balance but indirectly.Third rule: Assesment by the whole community

The assesment of cooperative projects should not be made by the person who facilitates its starting up, but by the entire community which will focus naturally on useful projects, well made and presented in an understandable way. If the project was initiated or supported by a representative, he will know its value of the project according to its progressive use by the targeted community.Fourth deviation: Objective assesment

Another danger with conventional assesment is the obligation to define objective assesment criteria which by definition approach what is desired without ever reaching it. Only objective factors are taken into account properly. The unmeasurable subjective elements such as good faith or motivation during the progress of the project are neglected, or worse, are subject to an accumulation of objective rules increasingly complex which favor the opposite effect.Example of country assessment: Rating indicators

Many evaluations are made for countries on financial means (rating indicators) such as Gross Domestic Product. There is a great temptation for policymakers to act directly on the assessed criteria rather than on their causes. GDPwill not enhance for example the difference between a country where the majority of wealth is in the hands of a small group of leaders and a country where wealth is better distributed. We try then to add more and more ''corrective'' financial criteria, but without encouraging the assessed leaders to act on causes rather than on assessed criteria.A very interesting approach was initiated by the United Nations Program for Development with a Human Development Index based on several criteria which approximate at best the object that is to be evaluated.

These criteria apprehend: health, education and economics.

This is probably our best today to assess human development in a country with an objective indicator, but each rate itself is a mean and only objective, measurable criteria are taken into account. It is then possible to educate better a privileged part of the population or to enroll without seeking to increase school performance indices. Multiplying criteria only makes the task more subtle for those who only strive to adapt their performance to optimize the values of each criterion. But it gives less chance to fulfill at the very best the specific criteria to the indicator for those who very honestly focus primarily on causes.

The traditional methods of objective measures achieved with the scientific advances of the XVIIth century itself require developments to go beyond simple means: sometimes we add standard deviations to average rates (average deviations from the mean). If it gives an idea of the scale of differences, some more subtle points are not taken into account, for example the homogeneous distribution of a population or the division into two or more groups more or less privileged with little chance to move from one group to another.

Side effects (the extreme limits) can also disturb simple objective laws (for example, monopolies). You must have an idea of what happens far from balance and even on limits.

Fourth rule: Reintroduce subjective evaluation

If the evaluation criteria are essential, especially when outsiders must objectively analyze the results, they are however insufficient. On the contrary, the long term collective assessment enables a direct promotion and expansion of a project by attracting new contributors every day, but it s ill suited for an objective assessment.The problem comes from impossibility to measure good faith objectively. It is only possible to obtain a measurable objective assessment afterwards and with greater or lesser margin between the measured result and the evaluation criteria.

Agrreing on the reintroduction of a subjective evaluation, such as the one provided by the esteem brought by a project, is essential. To lessen difficulties, it is important that it should be decentralized and global and obtained by the whole community and the outside world.

The end of coercive power allows an auto-regulated evaluation

Of course, the implementation of an evaluation afterwards, continuous, subjective and by the whole community seems insoluble if we keep a traditional approach of assesment. To get out of Peter's apparently insoluble paradoxes, we will need, as in the previous chapters, to propose a different environment which doesn't impose the same limits any more.In a cooperative project, we try to obtain the cooperation of the members and to coordinate their works to get a result. The power of constraint (hierarchical or contractual power), is not any more in the center of the management of the project. The end of the power of constraint allows an auto-regulated evaluation.

The pure and simple abolition of the coercive power may seem a heresy heading to the " field of mud " of the tragedy of commons. We will see on the contrary that in an appropriate environment, it allows to get out of usual paradoxes.

When we are not "forced to cooperate" any more, each one gets involved or uses the results according to what he sees of the project. If globally, the project generates esteem, it will develop more and more. The evaluation is then subjective, post factum and continuous by the whole community of the contributors and of the users. The whole creates a virtuous circle.

The power of the coordinator is limited to the ability of integrating or not the proposed changes by the contributors and possibly exclude a person from the community he established. For what's left, he can only encourage people to become user or contributor, with no power to compel them.

Collaborative projects are well suited to projects between structures or inter-service projects. The running of associations sometimes allow to develop non-hierarchical projects of this kind.

Other approaches

One of the difficulties with giving up the power of constraint is that it requires projects requiring a very low involvement when starting up, an environment of abundance and no deadlines nor expectation of a particular result. This is exactly criteria which allow the implementation of a cooperative project, as we started seeing it.The complete abandonment of power of constraint given by the title or the employment contract is replaced by the incentive to cooperate with the results obtained and esteem. This is a major difference with the conventional project management. It is therefore not easy to follow both approaches simultaneously. We will see in the chapter on mixing methods that projects using fully or partially the power of constraint can simply give some advantages in promoting the greatest possible post factum long term and subjective evaluation by the community.

Summary

Assessing a project can be done:- After the event (post factum)

- Continuously

- Apprehending subjective ideas

- By the entire community of contributors and users

This can be achieved by giving up the power of constraint and by letting esteem for the project and its members do its self-regulation job.

1 HARDIN, Garrett. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science [online]. 13 December 1968. Vol. 162, no. 3859, p. 1243–1248. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. DOI 10.1126/science.162.3859.1243. Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/162/3859/1243The population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality.PMID: 17756331

2 RAYMOND, Eric S. Homesteading the noosphere. First Monday [online]. 1998. Vol. 3, no. 10. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/621

3 "Hardin later recognized that much of his characterization of the negative aspects of the commons, which according to his analysis 'remorselessly generates tragedy'... was based on a description, not of a commons regime in which authority over use of the resources resides within the community, but of an open access regime, unregulated by any external authority or social consensus" : WARNER, Gary. Participatory Management, Popular Knowledge, and Community Empowerment: The Case of Sea Urchin Harvesting in the Vieux-Fort Area of St. Lucia. Human Ecology [online]. 1 March 1997. Vol. 25, no. 1, p. 29–46. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. DOI 10.1023/A:1021931802531. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A%3A1021931802531

4 MAUSS, Marcel and WEBER, Florence. Essai sur le don: forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques. Paris, France : Presses universitaires de France, 2007. Quadrige. Grands textes, ISSN 1764-0288. ISBN 978-2-13-055499-8.

5 GODELIER, Maurice. L’énigme du don. Paris, France : Fayard, impr. 1997, 1997. ISBN 2-213-59693-X.

6 See the journal "Pour la Science" which edits an article on the prisonner's dilemma every six months (Scientific American). Pour la Science - Le magazine de référence de l’actualité scientifique. [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://www.pourlascience.fr/

Voir aussi Le dilemme du prisonnier. [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://web.archive.org/web/20050302205551/http://www.apprendre-en-ligne.net/jeux/dilemme/home.html

7 WERBER, Bernard. L’encyclopédie du savoir relatif et absolu. Paris, France : Albin Michel, 2000. ISBN 2-226-12041-6.

8 GLANCE, Natalie and HUBERMAN, Bernardo. La dynamique des dilemmes sociaux. Pour la science [online]. 1994. No. 199, p. 26–31. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=4210574

9 GODELIER, Maurice. L’énigme du don. Paris, France : Fayard 1997. ISBN 2-213-59693-X.

BLONDEAU-COULET, Olivier and LATRIVE, Florent (eds.).

Libres enfants du savoir numérique: une anthologie du “Libre.”Paris, France : Ed. de l’Eclat, impr. 2000, 2000. Premier secours. - Perreux : L’Eclat. ISBN 2-8416-2043-3.

BARBROOK, Richard. L’économie du don High Tech. [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://web.archive.org/web/20090917124333/http://www.freescape.eu.org/eclat/2partie/Barbrook/barbrook2.html

10 GIRARD, René. Je vois Satan tomber comme l’éclair. Paris, France : B. Grasset, 1999. ISBN 2-246-26791-9.

11 GUYARD, Jacques, BRARD, Jean-Pierre and FRANCE. ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE. Rapport fait au nom de la Commission d’enquête sur la situation financière, patrimoniale et fiscale des sectes, ainsi que sur leurs activités économiques et leurs relations avec les milieux économiques et financiers. Paris, France : Assemblée nationale, 1999. Les Documents d’information - Assemblée nationale (Texte imprimé), ISSN 1240-831X ; 1999, 33. ISBN 2-11-108354-2.

12 "in a hierarchy, every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence." : PETER, Laurence J and HULL, Raymond. The Peter principle: why things always go wrong. New York : Bantam, 1969. ISBN 9780553244151.

See also an interview of J. Peters : The Peters Principles. Reason.com [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://reason.com/archives/1997/10/01/the-peters-principles

Source: CORNU, Jean-Michel. La coopération, nouvelles approches. http://www. cornu. eu. org/texts/cooperation [online]. 2004. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from: http://fing-unige.viabloga.com/files/cooperation2.pdf

Photo credits : StephanieHobson sur Flickr - CC-BY-SA