Facilitate convergence by establishing mechanisms of esteem

The Peter's principle

Laurence J. Peter studied the paradoxes which urge an organization going from bad to worse. His most known principle indicates that "In a hierarchy, every person tends to rise until she gets to her level of incompetence"

12

Indeed, when someone is appointed to a position and fulfills his task, he is promoted to a new position. The process continues, allowing him to practice his skills on increasingly complex tasks until he reaches a position where he has reached his "level of incompetence". He is then no longer able to fulfill his role as well and is no longer promoted. He then remains stuck to the position where he is the less competent.

This case is just one of many paradoxes that arise when one wishes to evaluate human labor as objectively as practical and scientific facts. From this point of view, the work of Taylor who made the most scientific planning is more adapted to machine than man. At the time this work was published, many people were working machines. Today, the machines are sophisticated enough to take over the most repetitive and schedulable work. In return, the task of creating, as well as those requiring high scalability and subjective estimation are undergoing a strong development.

There is absolutely no denying any evaluation but rather to find new methods that apprehend human characteristics better: subjectivity, motivation or lack of motivation, good or bad faith. These different criteria are peculiar because not measurable even if they can be estimated to a certain extent. So this is a true revolution in the evaluation systems in a world based on objective measures since the XVIIth century. However, we see that the same subjective evaluations can produce phenomena of regulation and self-correction that is their mainspring.

Evaluation of conventionnal projects

The purpose of assessment in a conventional management project is triple :

- Know beforehand whether a project can be given to someone or to a team

- Ensure that the project is corrected along its development to improve results

- Assess the project post factum to see if it was successful

Usually, in the industrial projects submitted to a call for tenders for example, the first and the last goals outdo. The investment of a representative being heavy, he tries to know beforehand if his money is well invested. During the project, he tries to correct it so that the project goes on well. Then finally, he assess if the result can be used for further stages (broadcasting of the results or basic contribution to another project following a ''taylorized'' assembly-line).

First deviation : Beforehand assesment

Often to attract contributors, they are given a "title" in the project. It often helps to motivate the person by bringing recognition from the very start. Beware though, titles have three dangers :

- It's a beforehand recognition which places us in the Peter's Principle

- They often give a coercive hierarchical power.

- They are dangerous when operating because they block a role that can not easily be taken over by another if necessary.

Ideally, the title given is not exclusive and does not give special power. A "binding agent with the Spanish-speaking world" (which does not preclude having other) is better than a "person in charge of translations into Spanish''.

First rule: Assess after the event (post factum)

Let's assume that a project is developped in an environment of abundance, the minimum necessary for its survival needs are fullfiled and that there is sufficient time to allow the group to mature at its own pace. In this case, the beforehand assesment is far less important (except perhaps for the one in charge of the project who must decide whether to launch it or not). In this case it is more useful to correct the project along its development.

Similarly the final assesment is often about assessing the realization of what was expected beforehand rather than judging its usefulness and the use that is made afterwards.

Assesment during the progress of the project may instead provide a mechanism for self-correction afterwards to maximize the use made of the results already achieved by the project. Potential contributors will be involved according to their personal evaluation of the project, of the coordinator and of what they can gain from the results.

Second deviation: Limited assesment

The assesment is usually done at specific times, just like a photo of the project, sometimes only before and after the project. In this case, it doesn't apprehend human evolutions that even small at the start may swell quickly then suddenly switch to cooperation or betrayal. It does not allow to seize opportunities early enough at the source.

Second rule: Continuous assesment

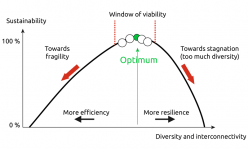

When allowing continuous assessment, we enable the emergence of vicious or virtuous circles "that will magnify until a brutal change of behavior. According to the observers' insight (and we will see in the next section that many people are better than one in this case), differences can be detected early enough to act accordingly.

Third deviation: Assesment by a reduced number of persons

Often, the project is assessed by representatives who want to know if their money is well invested. The evaluation is done by an external person (an agent) which ''only needs'' to be convinced with a well presented report on what will be done or the expected results. Of course during and at the end of the project, actual results are also included in the balance but indirectly.

Third rule: Assesment by the whole community

The assesment of cooperative projects should not be made by the person who facilitates its starting up, but by the entire community which will focus naturally on useful projects, well made and presented in an understandable way. If the project was initiated or supported by a representative, he will know its value of the project according to its progressive use by the targeted community.

Fourth deviation: Objective assesment

Another danger with conventional assesment is the obligation to define objective assesment criteria which by definition approach what is desired without ever reaching it. Only objective factors are taken into account properly. The unmeasurable subjective elements such as good faith or motivation during the progress of the project are neglected, or worse, are subject to an accumulation of objective rules increasingly complex which favor the opposite effect.

Example of country assessment: Rating indicators

Many evaluations are made for countries on financial means (rating indicators) such as Gross Domestic Product. There is a great temptation for policymakers to act directly on the assessed criteria rather than on their causes. GDPwill not enhance for example the difference between a country where the majority of wealth is in the hands of a small group of leaders and a country where wealth is better distributed. We try then to add more and more ''corrective'' financial criteria, but without encouraging the assessed leaders to act on causes rather than on assessed criteria.

A very interesting approach was initiated by the United Nations Program for Development with a Human Development Index based on several criteria which approximate at best the object that is to be evaluated.

These criteria apprehend: health, education and economics.

This is probably our best today to assess human development in a country with an objective indicator, but each rate itself is a mean and only objective, measurable criteria are taken into account. It is then possible to educate better a privileged part of the population or to enroll without seeking to increase school performance indices. Multiplying criteria only makes the task more subtle for those who only strive to adapt their performance to optimize the values of each criterion. But it gives less chance to fulfill at the very best the specific criteria to the indicator for those who very honestly focus primarily on causes.

The traditional methods of objective measures achieved with the scientific advances of the XVIIth century itself require developments to go beyond simple means: sometimes we add standard deviations to average rates (average deviations from the mean). If it gives an idea of the scale of differences, some more subtle points are not taken into account, for example the homogeneous distribution of a population or the division into two or more groups more or less privileged with little chance to move from one group to another.

Side effects (the extreme limits) can also disturb simple objective laws (for example, monopolies). You must have an idea of what happens far from balance and even on limits.

Fourth rule: Reintroduce subjective evaluation

If the evaluation criteria are essential, especially when outsiders must objectively analyze the results, they are however insufficient. On the contrary, the long term collective assessment enables a direct promotion and expansion of a project by attracting new contributors every day, but it s ill suited for an objective assessment.

The problem comes from impossibility to measure good faith objectively. It is only possible to obtain a measurable objective assessment afterwards and with greater or lesser margin between the measured result and the evaluation criteria.

Agrreing on the reintroduction of a subjective evaluation, such as the one provided by the esteem brought by a project, is essential. To lessen difficulties, it is important that it should be decentralized and global and obtained by the whole community and the outside world.

The end of coercive power allows an auto-regulated evaluation

Of course, the implementation of an evaluation afterwards, continuous, subjective and by the whole community seems insoluble if we keep a traditional approach of assesment. To get out of Peter's apparently insoluble paradoxes, we will need, as in the previous chapters, to propose a different environment which doesn't impose the same limits any more.

In a cooperative project, we try to obtain the cooperation of the members and to coordinate their works to get a result. The power of constraint (hierarchical or contractual power), is not any more in the center of the management of the project. The end of the power of constraint allows an auto-regulated evaluation.

The pure and simple abolition of the coercive power may seem a heresy heading to the " field of mud " of the tragedy of commons. We will see on the contrary that in an appropriate environment, it allows to get out of usual paradoxes.

When we are not "forced to cooperate" any more, each one gets involved or uses the results according to what he sees of the project. If globally, the project generates esteem, it will develop more and more. The evaluation is then subjective, post factum and continuous by the whole community of the contributors and of the users. The whole creates a virtuous circle.

The power of the coordinator is limited to the ability of integrating or not the proposed changes by the contributors and possibly exclude a person from the community he established. For what's left, he can only encourage people to become user or contributor, with no power to compel them.

Collaborative projects are well suited to projects between structures or inter-service projects. The running of associations sometimes allow to develop non-hierarchical projects of this kind.

Other approaches

One of the difficulties with giving up the power of constraint is that it requires projects requiring a very low involvement when starting up, an environment of abundance and no deadlines nor expectation of a particular result. This is exactly criteria which allow the implementation of a cooperative project, as we started seeing it.

The complete abandonment of power of constraint given by the title or the employment contract is replaced by the incentive to cooperate with the results obtained and esteem. This is a major difference with the conventional project management. It is therefore not easy to follow both approaches simultaneously. We will see in the chapter on mixing methods that projects using fully or partially the power of constraint can simply give some advantages in promoting the greatest possible post factum long term and subjective evaluation by the community.

Summary

Assessing a project can be done:

- After the event (post factum)

- Continuously

- Apprehending subjective ideas

- By the entire community of contributors and users

This can be achieved by giving up the power of constraint and by letting esteem for the project and its members do its self-regulation job.

1 HARDIN, Garrett. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science [online]. 13 December 1968. Vol. 162, no. 3859, p. 1243–1248. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. DOI 10.1126/science.162.3859.1243. Available from:

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/162/3859/1243The population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality.PMID: 17756331

2 RAYMOND, Eric S. Homesteading the noosphere. First Monday [online]. 1998. Vol. 3, no. 10. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from:

http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/621

3 "Hardin later recognized that much of his characterization of the negative aspects of the commons, which according to his analysis 'remorselessly generates tragedy'... was based on a description, not of a commons regime in which authority over use of the resources resides within the community, but of an open access regime, unregulated by any external authority or social consensus" : WARNER, Gary. Participatory Management, Popular Knowledge, and Community Empowerment: The Case of Sea Urchin Harvesting in the Vieux-Fort Area of St. Lucia. Human Ecology [online]. 1 March 1997. Vol. 25, no. 1, p. 29–46. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. DOI 10.1023/A:1021931802531. Available from:

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A%3A1021931802531

4 MAUSS, Marcel and WEBER, Florence. Essai sur le don: forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques. Paris, France : Presses universitaires de France, 2007. Quadrige. Grands textes, ISSN 1764-0288. ISBN 978-2-13-055499-8.

5 GODELIER, Maurice. L’énigme du don. Paris, France : Fayard, impr. 1997, 1997. ISBN 2-213-59693-X.

6 See the journal "Pour la Science" which edits an article on the prisonner's dilemma every six months (Scientific American). Pour la Science - Le magazine de r√©f√©rence de l’actualit√© scientifique. [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from:

http://www.pourlascience.fr/

Voir aussi Le dilemme du prisonnier. [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from:

http://web.archive.org/web/20050302205551/http://www.apprendre-en-ligne.net/jeux/dilemme/home.html

7 WERBER, Bernard. L’encyclopédie du savoir relatif et absolu. Paris, France : Albin Michel, 2000. ISBN 2-226-12041-6.

8 GLANCE, Natalie and HUBERMAN, Bernardo. La dynamique des dilemmes sociaux. Pour la science [online]. 1994. No. 199, p. 26–31. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from:

http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=4210574

9 GODELIER, Maurice. L’énigme du don. Paris, France : Fayard 1997. ISBN 2-213-59693-X.

BLONDEAU-COULET, Olivier and LATRIVE, Florent (eds.).

Libres enfants du savoir numérique: une anthologie du “Libre.”Paris, France : Ed. de l’Eclat, impr. 2000, 2000. Premier secours. - Perreux : L’Eclat. ISBN 2-8416-2043-3.

BARBROOK, Richard. L’√©conomie du don High Tech. [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from:

http://web.archive.org/web/20090917124333/http://www.freescape.eu.org/eclat/2partie/Barbrook/barbrook2.html

10 GIRARD, René. Je vois Satan tomber comme lՎclair. Paris, France : B. Grasset, 1999. ISBN 2-246-26791-9.

11 GUYARD, Jacques, BRARD, Jean-Pierre and FRANCE. ASSEMBL√ČE NATIONALE. Rapport fait au nom de la Commission d’enquête sur la situation financière, patrimoniale et fiscale des sectes, ainsi que sur leurs activités économiques et leurs relations avec les milieux économiques et financiers. Paris, France : Assembl√©e nationale, 1999. Les Documents d’information - Assembl√©e nationale (Texte imprim√©), ISSN 1240-831X ; 1999, 33. ISBN 2-11-108354-2.

12 "in a hierarchy, every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence." : PETER, Laurence J and HULL, Raymond. The Peter principle: why things always go wrong. New York : Bantam, 1969. ISBN 9780553244151.

See also an interview of J. Peters : The Peters Principles. Reason.com [online]. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from:

http://reason.com/archives/1997/10/01/the-peters-principles

Source: CORNU, Jean-Michel. La coopération, nouvelles approches.

http://www. cornu. eu. org/texts/cooperation [online]. 2004. [Accessed 30 January 2014]. Available from:

http://fing-unige.viabloga.com/files/cooperation2.pdf

Photo credits : StephanieHobson sur Flickr - CC-BY-SA